JapanDownUnder

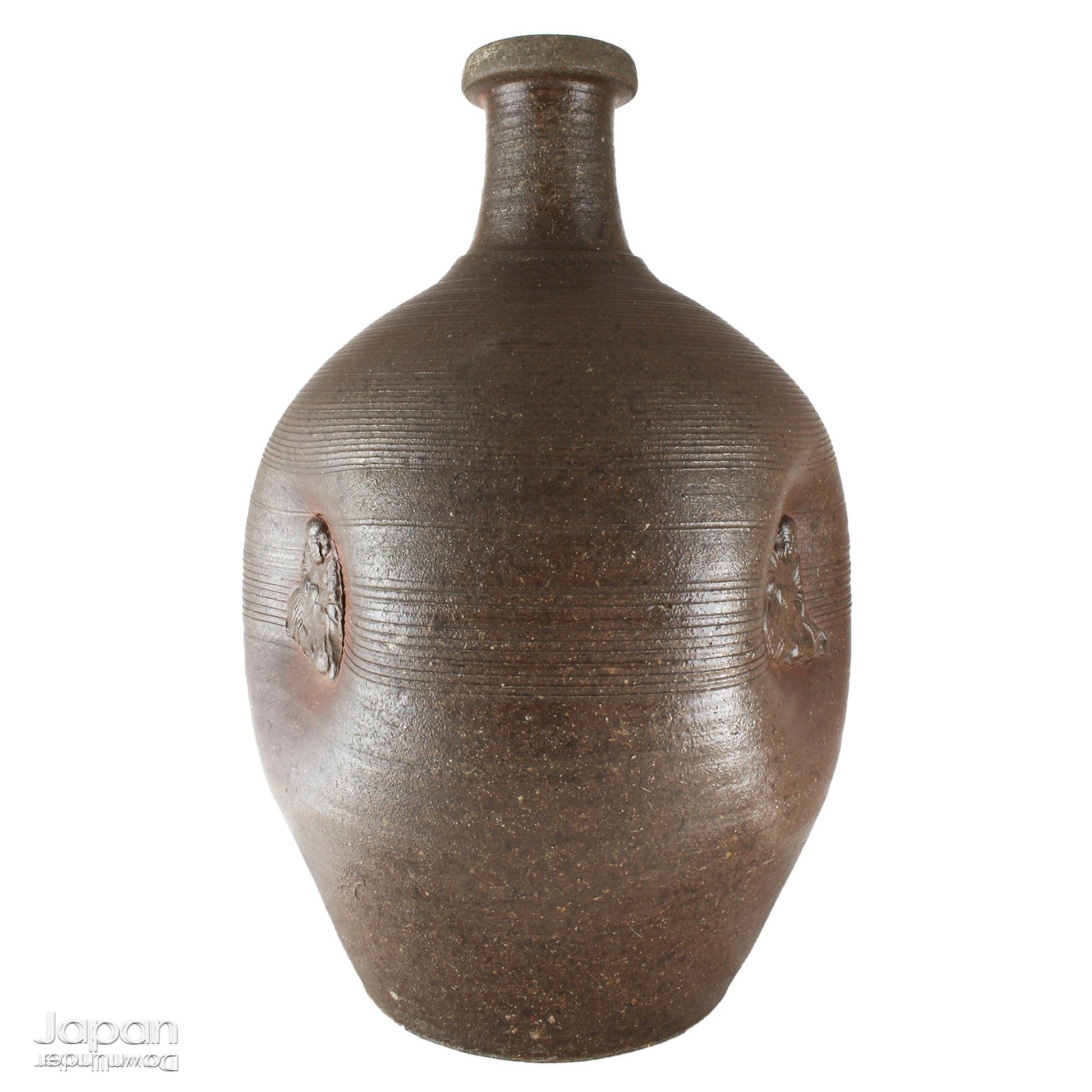

large antique bizen sake bottle with lucky god hotei - japanese vase and art object

large antique bizen sake bottle with lucky god hotei - japanese vase and art object

Couldn't load pickup availability

Love Japanese Style Like We Do

Add depth and story to your interior with this striking Taisho-era Bizen ware sake tokkuri, adorned with Hotei - the cheerful god of happiness, children, and good fortune, and one of Japan’s beloved Seven Lucky Gods. More than just a vessel, this antique bottle is a captivating example of Japanese folk craftsmanship, equally compelling as a sculptural display piece or a uniquely soulful vase.

This is a Kayoi Tokkuri, part of a remarkable tradition that stretches back to the Edo period. In those days, customers brought their own ceramic bottles to sake shops for refills - a practice both practical and sustainable, echoing early eco-conscious values. The term Kayoi means “to commute,” and Tokkuri refers to the sake-carrying bottle - making this piece a functional slice of everyday history.

Handcrafted in the esteemed Bizen tradition - one of Japan’s Six Ancient Kilns - this tokkuri is a classic example of unglazed, wood-fired stoneware. Its surface bears the natural ash glaze and expressive fire markings that result from the long, high-temperature firing process unique to Bizen pottery. Valued for its earthy textures, warmth, and incredible durability, Bizen ware has been admired for centuries.

Substantial in size and weight, this bottle features a bulbous body that gently tapers into an elongated neck. Subtle concentric rings are incised around the upper portion, while the belly has been softly pressed into a triangular form - a detail that adds visual rhythm and tactility. Nestled within each of these three indentations is a relief of Hotei, his smiling form lending charm and auspicious meaning to the piece.

Originally made for everyday use by ordinary people, the piece reflects the humble roots of Japanese folk kilns. The finish is rustic and organic, with no kiln mark - typical of early Bizen works. Structurally sound with no cracks or chips, it shows only a gentle patina from use and age - the kind of surface wear that imbues it with warmth and authenticity.

While such bottles were once considered mundane household items, the Mingei (folk art) movement - founded by philosopher Soetsu Yanagi in 1926 - redefined their significance. Mingei celebrated the quiet beauty of handmade, utilitarian objects, crafted by unknown artisans in harmony with nature. Today, pieces like this are prized for their raw elegance and cultural resonance.

Whether placed on the floor, a low bench, or a shelf, this tokkuri commands attention - a conversation-starting relic with rich heritage and an understated, sculptural presence.

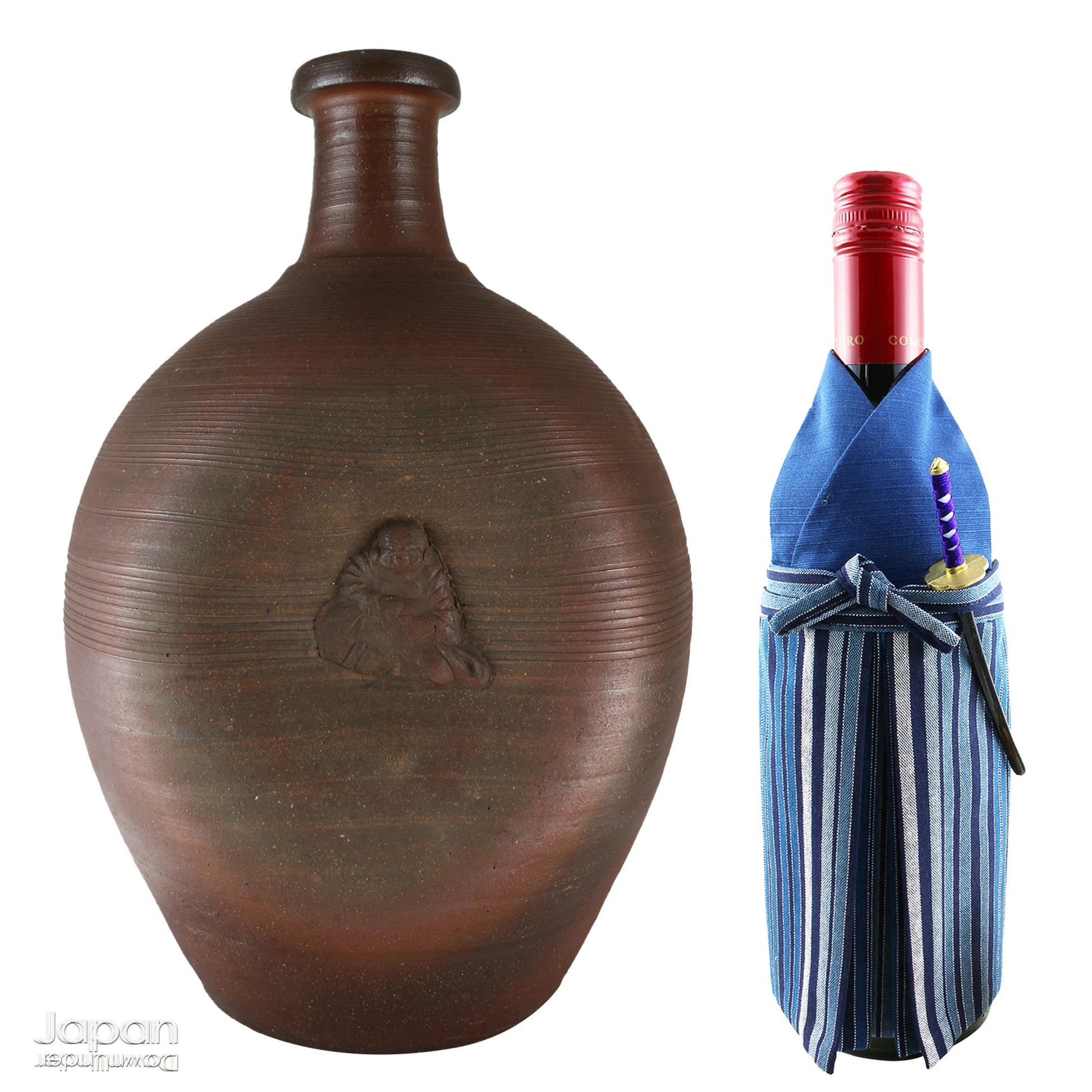

- measures around 33.5 cm (13.2”) tall x 23 cm (9”) in diameter.

- weighs 2,400 gm (5.3lbs).

(listing for bizen sake bottle only)

SHIPPING INFORMATION

- please read the shipping notes in our shop announcement.

- we use recycle packaging wherever possible and wrap for safety, rather than appearance!

ABOUT OUR VINTAGE, ANTIQUE AND OTHER ITEMS

We list pieces we feel are worthy of display. There may be scratches, dents, fading and signs of wear and tear. We try to explain the condition of each item exactly, but may miss something.

Information regarding the item and it’s age is obtained from dealers and our personal research. We do our best to give you the correct information but please be aware that we cannot guarantee this information.

Please message us prior to purchase with any questions you may have about our products.

KAYOI TOKKURI

From ancient times sake was regarded as a special beverage, made from precious rice. It was drunk, not only for its intoxicating and festive nature, but also as a symbol of purification and starting anew at religious ceremonies.

It is believed the first alcoholic beverage was made in the Yayoi period (300 BC - 250 AD). During the Nara period (710-794) sake was produced for the Imperial Court and during the Heian period (794-1185) sake was made by temples and shrines and home brewed in farming villages. Sake breweries started in the Muromachi period (1333-1573), together with the technology to make large wooden storage barrels. By the Edo period (1603-1868) sake manufacturing had become a thriving industry with techniques to improve the flavor and preserve the liquor.

It was during the Edo period that the custom of dispensing sake to regular customers, using the kayoi tokkuri became popular for liquor stores. The kayoi tokkuri was a sturdy stoneware or porcelain bottle with either a bulborous body or thinner cylindrical body and a long, thin neck. Written on the body of the bottles, in large Japanese script was the liquor store’s name and address, their brand of sake and trademark. The bottles were only lent to customers and sometimes ‘not for sale ‘ was also written.

Sake was shipped from breweries and sent to liquor stores through the wholesaler. Customers went to the liquor store to buy their sake returning home with a full bottle. Once the bottle was empty they went back to the shop where the kayoi tokkuri was once again filled. ‘Kayou’, actually means to commute and ‘tokkuri’ refers to the container, that was carried to and from the shop and customers home. At this time, stoneware Mino tokkuri were mainly used in Eastern Japan, and the use of Tamba-Tachikui stoneware and Arita porcelain ware spread in Western Japan.

At the beginning of the Meiji era the government revised its tax laws and sake tax greatly increased. In 1889 home brewing was completely banned with the idea that home brewers would have to buy their sake from liquor stores, thus increasing the amount of tax the government could collect. The kayoi tokkuri, often also known as the ‘bimbo tokkuri,’ (poor mans sake bottle), enabled people with not so much money to buy just the amount of the expensive sake they needed, as sake was sold by the weight.

With no other way to drink sake than to buy it, the demand for kayoi sake bottles increased. Kilns everywhere, well know for their rapid response to trends, soon started to produce more kayoi sake bottles enabled by the spread of improved railway networks, allowing their wares to be sent nation wide. There were Mino, Shigaraki, Tanba, Otani, Bizen, Tobe, Ushinoto and other tokkuri produced in Eastern Japan and Arita/Imari porcelain tokkuri produced in Kyushu.

Sadly, the kayoi tokkuri was replaced by a glass bottle after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and gradually disappeared. Looking at these old sake bottles now, we can imagine the lives of people in the past and the joy they must have had drinking with friends and family on festive occasions.

BIZEN HISTORY

Bizen roots are the unglazed Sueki earthenware vessels of the Oku region. Sueki stoneware was made using techniques that came from Korea in the Kofun, (250 AD - 538 AD), Nara (71 AD - 784 AD) and Heian (794 AD - 1185) periods. It was fired in an anagama at high temperatures and was generally grayish brown in colour.

In the latter Heian period the sword industy flourished and as a result the scarcity of firewood intensified. Sueki potters moved to Imbe in search of wood for their kilns. Artistic Sueki ware was abandoned and pottery that was necessary for people’s daily lives was produced, giving birth to Bizen pottery. At this time Bizen ware consisted of mainly containers, mortar bowls and jars.

From the Kamakura period (1185 - 1333) into the Muromachi period,(1333 - 1573). Bizen pottery faced an age of unprecedented mass production and purchasing. The kilns that were once up in the mountains moved further down to the foot of the mountains. By the end of the Muromachi period the mountain clay used for Bizen pottery shifted to the use of clay from rice paddies.

Demand for Bizen ware increased and so did popularity, Goods had to be loaded and sent off from the harbour, so kilns gradually moved closer to Imbe village for convenient transportation. Bizen gained the reputation as a tough and sturdy ceramic with people saying, ‘even if you throw a Bizen earthenware mortar, it doesn’t break.’ Everyday wares were fired in large quantities and Bizen spread to various regions in Japan.

From the late Muromachi period into the Momoyama period, (1573-1603), masters of the tea ceremony, who had no utensils for their art, discovered aesthetic beauty in practical Bizen ware containers. By selecting Bizen ware, for use in the tea ceremony, as water jars and flower vases, Bizen daily articles grew ever more popular.

From around the Genwa year of the Edo period (1615-24), Bizen Pottery began to show signs of its prolonged decline. Tea ceremony tastes moved towards the new, more elegant and refined porcelains of Arita, Seto and Kyoto ware. Bizen was seen as crude and ugly with its exposed reddish, earthy surface. Bizen potters focused on producing ornaments that replaced the popular tea-wares of before.

In order to compete against porcelain, the technique of ‘Inbe-de’ was developed, giving pieces a lustre like that of glazed ware or copper ware. White Bizen, celadon, and colored bizen, known as Shizutani ware were also made. Shizutani pottery did not succeed and demand for Bizen pottery declined to the extent that large communal kilns could not be fired.

From the Bunmei Kaika in Meiji (1868- 1912). the age of civilization and enlightenment, European ways flourished and the traditional culture of Japan was given lower regard. Crude, earthy, undecorated wares like Bizen were not in demand. With the development of transportation systems, glazed porcelain wares of Seto and Arita could be obtained at reasonable prices and this hastened the departure from Bizen wares. Although difficult to imagine the goods that were produced in the largest quantities by kilns in Imbe were earthenware pipes and bricks!

After World War 1, the Japanese economy reached a stage where it could stand equally alongside the nations of Europe and America. The decline in the appreciation of Japanese traditional culture was reassessed with much enthusiasm. Tea ceremony became popular amongst the newly emerging wealthy class. Tea bowls, water jars and vases were in demand and the tea wares that this class craved were Seto, Mino, Iga, Karatsu and Bizen ware pieces from the Momoyama period.

For Bizen, there was one potter who paid attention to the tea wares of the Momoyama period. His name was Kaneshige Toyo (1896-1967). Toyo, who had once been famous in figurative handiwork decided to focus on the ‘return to Momoyama’ in his mid 30’s and began to recreate famous wares of Momoyama Bizen. Thanks to Toyo’s existence, potters of the same generation were also greatly encouraged and from this, successive potters continued to thrive under his influence. As a result, potters pursue their art independently in Bizen and it is said that there are now approximately 400 potters producing Bizen wares around Imbe.

Share