JapanDownUnder

rare japanese antique kamidana shinto shrine with tenjin god of learning - spiritual folk art

rare japanese antique kamidana shinto shrine with tenjin god of learning - spiritual folk art

Couldn't load pickup availability

Love Japanese Style Like We Do

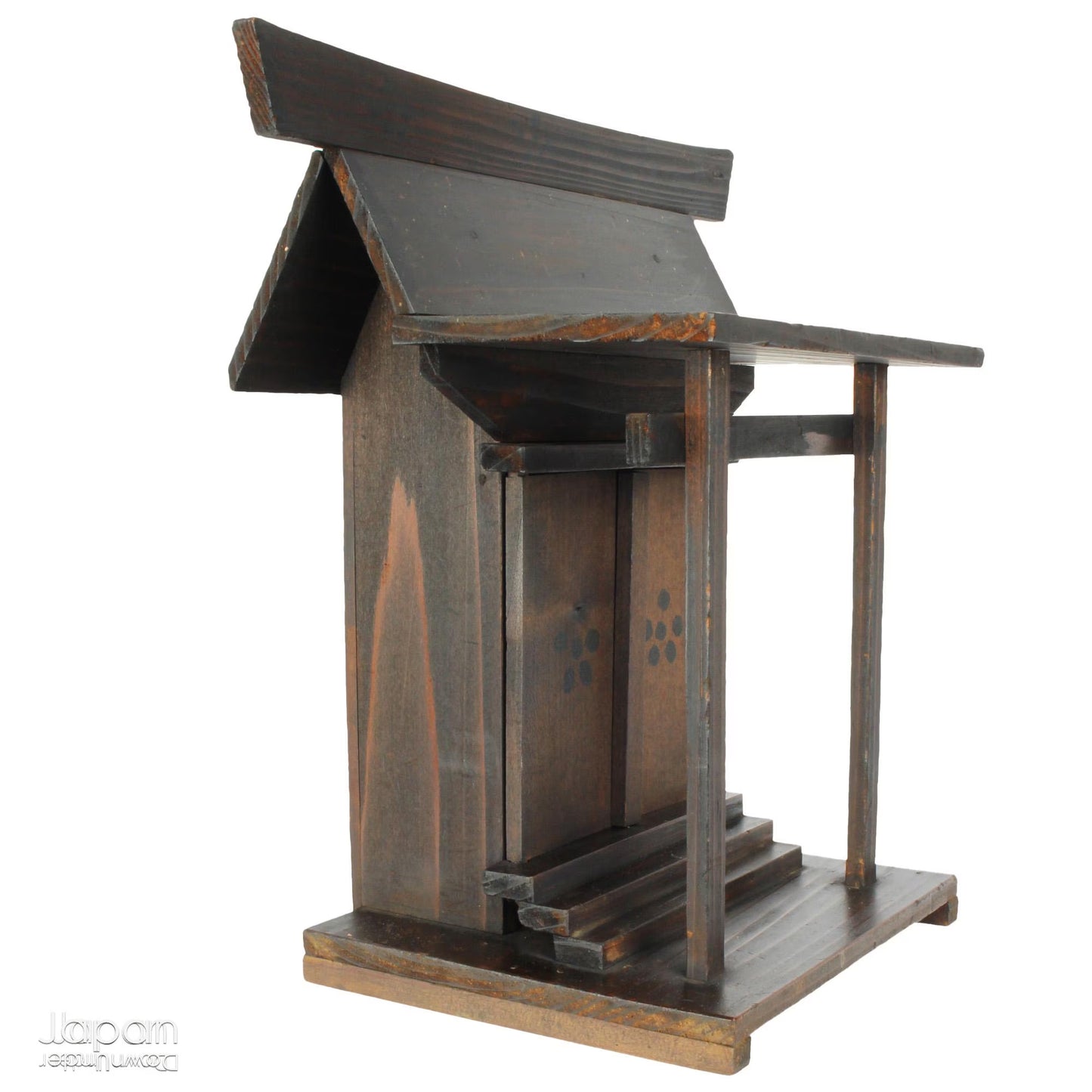

Add a meaningful touch to your spiritual space with this rare and beautifully rustic antique Shinto shrine. Crafted for placement on a kamidana (god shelf), this handcrafted zushi houses Tenjin, the beloved kami of learning, flanked by his divine protectors. Radiating serene energy, it captures the essence of Shinto folk tradition and serves as both a sacred object and a deeply evocative piece of Japanese heritage.

This extraordinary kamidana features a traditional Zuishin-mon (guardian gate) in front of the shrine doors. Two clay Zuishin guardians - Yadaijin and Sadaijin - stand sentry on either side of the gate, protecting the enshrined deity from evil with their sword and bow and arrow. Between them rests a small shinkyo, a reflective metal mirror symbolizing the presence of the divine. The craftsmanship and symbolism reflect a deep reverence for spiritual balance and protection.

Inside the wooden shrine resides a clay figure of Tenjin - the deified form of Sugawara no Michizane (845–903), a noble scholar and poet. In Shinto belief, Tenjin is the kami of academics and learning, a patron of students and travelers, and a once-feared sky deity associated with natural forces. His worship continues today in over 12,000 shrines across Japan, including the famed Kitano Tenmangu (Kyoto), Dazaifu Tenmangu (Kyushu), and Hofu Tenmangu (Yamaguchi).

Tenjin is seated on his characteristic striped platform, dressed in a traditional black shozoku (Shinto priest’s robes), and wearing a tall eboshi hat. He holds a shaku (ritual baton) and a sword - symbols of authority and spiritual guidance.

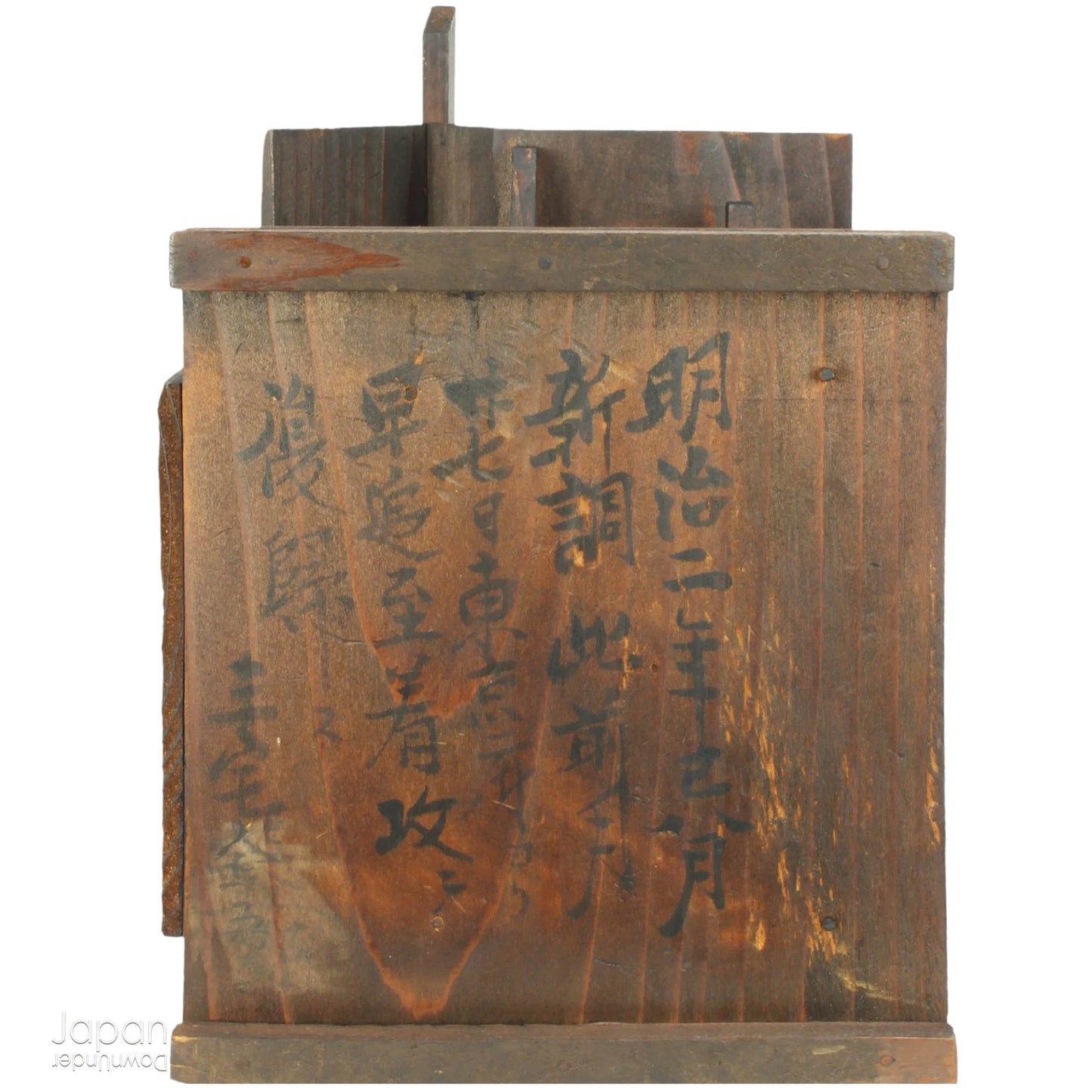

The shrine itself is crafted from light hinoki (Japanese cypress), known for its subtle grain and pleasant scent. An extended base and overhanging roof support the Zuishin gate, while small steps lead to the shrine’s main chamber. Delicate plum blossom motifs are painted on the front doors, a poetic tribute to Michizane’s deep love for plum trees. On the underside of the shrine, the date of purchase - Meiji 2 (1869) - is handwritten, marking it as a true historical artifact.

While the piece shows signs of age - minor wear to the wood, fading of painted details, flaking on the clay statues, and rusting of the shinkyo mirror - its structural integrity remains intact, and its spiritual presence undiminished.

A rare and evocative find for collectors of Shinto relics, Japanese antiques, or spiritual artifacts. This shrine not only honors a long-revered kami but also invites peace, reflection, and blessings into your home.

- shrine measures 29 cm (11.4”) tall x 18 cm (7.1”) across x 16 cm (6.3”) deep.

- weighs 650 gm.

SHIPPING INFORMATION

- please read our shipping notes in shipping policy.

- we use recycle packaging and wrap for safety, rather than appearance.

ABOUT OUR VINTAGE, ANTIQUE AND OTHER ITEMS

We list pieces we feel are worthy of display. There may be scratches, dents, fading and signs of wear and tear. We try to explain the condition of each item exactly, but may miss something.

Information regarding the item and it’s age is obtained from dealers and our personal research. We do our best to give you the correct information but please be aware that we cannot guarantee this information.

Please message us prior to purchase with any questions you may have about our products.

TENJIN

Tenjin is the deification of Sugawara Michizane (845–903). A famous poet, nobleman and politician, he fell out of favor with the emperor and was exiled from Kyoto far away to Kyushu. He died while in exile, and it is said that his spirit turned into a vengeful ghost. Immediately after his death, the capital (Kyoto) was struck by fire, storms and plague. A number of important people, connected to Sugawara’s exile, suddenly died. The court magicians and priests blamed these disasters on the angry ghost of Sugawara. In order to placate his spirit, he was enshrined as a god and called Tenjin.

Tenjin was ranked very high as a god and seen first as a sky deity and a god of natural disasters, worshipped to placate him and avoid his curses. Eventually, Tenjin’s status as a scholar and a poet during life, lead him to become the now popular kami (god) of education and scholarship. He is prayed to by parents and students during exam periods. A figure of Tenjin is often given as a present to newly borns in the hope of their future academic success.

Michizane was very fond of ume trees, writing a famous poem from exile in which he lamented the absence of a particular plum tree he had loved in Kyoto. Legend states that the tree flew from Kyoto to Dazaifu Shrine in Kyushu to be with him. The tree is still on show at his shrine there. As a result, shrines to Tenjin are often planted with many ume trees. By coincidence, these trees blossom in February, the same time of year as exam results are announced, and so it is common for Tenjin shrines to hold a festival around this time.

When exiled to Kyushu, Sugawara Michizane made the long journey from Kyoto to Dazaifu without encountering difficulties, so he has also come to be revered as a protecting god of travel and traffic safety.

SHINTO MIRROR (SHINKYO)

The circular mirror of Shinto is a potent symbol. It stands on the altar reresenting the kami (god). It also functions as the ‘spirit-body’ (goshintai) of the kami. It is the object the spirit enters to take physical form. The mirror acts as an interface between the physical and spiritual realms of existence.

Japanese mythology claims that the original ‘spirit-body’ was that of Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, who gave a circular mirror to her grandson, Ninigi, when he descended to earth. It had been used previously to lure her out of a cave in which she was hiding. Her absence had plunged the world into darkness, and to tempt her out she was told that there was another goddess as beautiful as herself. The mirror was held up so that when she peeked out she was greeted by her own radiance, and the momentary hesitation allowed a rope to be tied across the cave entrance to prevent her from re-entering. Sunlight was restored to the world.

Later when Amaterasu decreed that a mission be sent down to earth from the High Plains of Heaven, her grandson Ninigi-no-mikoto was chosen to lead it. Before he departed, she presented him with the very same mirror which had played such an important part in the rock-cave incident. ‘Take this and revere it as if it were myself,’ she told him. Within the reflecting surface something of her essence had become ingrained.

Ninigi passed the mirror down to his heirs, who formed the imperial line which continues to this day (the present emperor is the 125th). For a long time the mirror was kept in the palace of the king of Yamato, the dominant state in ancient Japan, but in the early centuries of the Common Era it was deposited at Ise Jingu. Since that time it has been kept secluded from human eye, acting as the unseen focus of worship for the millions of pilgrims and worshippers who file before it each year.

KAMIDANA

Kamidana, literally god shelf, or sacred shelf, are miniature household altars used to place an enshrined Shinto kami (god). Paper talismen, kamifuda and amulets, issued by the major Shinto shrines, were enshrined for worship to the kami. They became popular in traditional country style minka houses.

Small shrines for tutelary deities, inside a residence, go back to ancient times among the aristocracy. The emergence of the kamidana was closely connected with the development of the domestic Buddhist altar or butsudan, which started the movement of conducting religious rituals in each household.

Kamidana were initially set up to keep Jingu Onusa, charms of the Grand Shrine of Ise, when they began to be widely distributed at the end of the Muromachi period. The Jingu Onusa symbolized Amaterasu Omikami and were considered objects of worship. A special domestic shelf, to respect these charms, was installed and was called Jingu no tana, or shelf of the Grand Shrine. By the mid-Edo era, the institution of the kamidana had spread to most homes as a result of the spread of this Ise cult.

The most common style of kamidana was a plain board forming a shelf, supported by cantilevered brackets from beneath, or stabilized with timber hangers, suspended from the beams above. On this shelf a miniature Shinto shrine was installed to contain the kamifuda. This shrine could be elaborate in design, but unlike the miniature shrine cabinet, or zushi, of the Buddhist altar, the timber was unlacquered. The kamifuda enshrined was that of a clan deity or came from one of the major national shrines.

Kamidana were most often located in a high place, thought to be closest to the heavens and gods, in an area close to an earth floor. As old country kitchens had an earth floor and were a place where many people gathered, they were perfect for the kamidana and prayer. Candles were lit and offerings of rice, fruit, fish, rice and wine were made daily.

Particularly in the homes of farmers, fishermen, merchants and other craftsmen, additional deities with combined Shinto and Buddhist identities found their way to the kamidana. Ebisu and Daikoku-dana were popular. Ebisu, the god of fishing and Daikoku, the god of farming, were particular favorites amongst country folk, whose livelihood depended on agriculture and the ocean. Ebisu and Daikoku were often housed together in a special shrine with a rounded roof, and came to be known as the kitchen gods. Kojin-dana was another popular choice. Kojin was the god of domestic tranquility and good fortune. Inari-dana were also seen. Inari is the Japanese Shinto god who watches over and protects the rice harvest. A temporary toshitoku-dana was set up in almost all homes at the end of the year to welcome and worship the kami of the New Year.

Old Kamidana shrines are a wonderful example of Japanese mingei; a spiritual tool that reminds us of culture and customs of the past.

Share